A/Commissioner Thomas Caulkin

Thomas Cauklin distinguished himself in everything he did. Regardless of the challenge or hardship, he remained a dedicated member of the Force.

In 1919, he was the first member of the Force to receive the Kings’ Police Medal which was commonly referred to as the “policeman’s Victoria Cross.”

Thomas Benjamin Cauklin was born on April 29, 1886 at Wolverhampton England. His parents were Joseph Henry Cauklin and Emma Cauklin (Silitoe). After graduating from high school, Thomas joined and served 3 years with the Worcestershire Regiment (Imperial Army Reserve) .

To expand his sense of adventure, he travelled to Canada and made his way to Winnipeg Manitoba where he joined the Royal Northwest Mounted Police on April 19, 1907 and was issued the regimental #4557.

After completing training at Regina, he was sent to Lethbridge Alberta where he served at: Pendant d’oreille, Warner, Sundial and Medicine Hat. On April 10, 1909, he was promoted to Corporal and then to Sergeant on May 1, 1912. In October 1913, he was moved to Maple Creek Saskatchewan as acting Srgeant Major of “A” Division and he attained that rank on Jan 30, 1914.

In that same year, the Force received news that in 1911 one American hunter named Harry Radford and a young Canadian surveyor namd George Street had been killed by their Inuit guides at Bathurst Inlet.

Superintendent Starnes (Reg. O.71) to the Commissioner outlined that the area where the murders took place was a peculiarly inaccessible area in the arctic and the efforts to get there would be difficult and tedious. It was estimated that the capture of those responsible would take ‘the best part of two years.’ Starnes suggested that the investigative team consist of one officer, one non-commissioned officer, two or three constables and a good interpreter.

Commissioner Bowen Perry sought the approval from the Force Comptroller to proceed with the investigative expedition. In early 1914, the Canadian government approved for the Bathurst Inlet Expedition to commence.

Based on the government’s approval, this first Expeditionary Team was formed and consisted of: Inspector Walter Beyts (Reg. #2866 – O.161), Sergeant Major Thomas Caulkin (Reg #4557), Constable Alfred B. Kennedy (Reg. #5626) and Constable Ernest Pasley (Reg. #5720).

The Expeditionary Team departed Regina on a train heading to Halifax harbour. On March 10, 1915, the team left Halifax on the schooner ‘Village Belle’ and arrived at Chesterfield Inlet (Hudson Bay) in the late season. In the winter of 1915-16, the investigative team made two unsuccessful attempts to travel from Baker Lake to Bathurst Inlet.

The Expeditionary Team experienced extreme weather conditions and it was not until 1915 that this patrol established a base camp on Baker Lake. Weather conditions and a scarcity of caribou prevented further patrols.

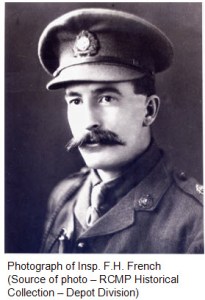

With multiple problems with this Expeditionary Team and the illness of Beyts, Inspector Frank French (Reg. #4355 – O.163) was sent in 1916 to replace Insp. Beyts.

Prior to departing Regina, Insp. French was given direction from the Commissioner – “It will be your duty to get in touch at the earliest possible moment with the tribes said to be responsible for the deaths. You will make inquiries and take such statutory declarations as may seem necessary in order a full and accurate account of the occurrence (murders). From information received, it is assumed that there was provocation. If this is found to be the case, it is not the intention of the Government to proceed with prosecution. If, however, there was found to be no provocation, the Government will consider what further action is to be taken.”

Upon taking command of the Expeditionary Team, Insp. French changed the composition of the team by retaining Sergeant Major Thomas Caulkin and dropping the two constables who were replaced by four Inuits with 20 dogs.

They then set out on what became the longest dog team patrol in the history of the Force – 5,153 miles which was covered by dog sled, walking and canoeing. They left Baker Lake on March 21, 1917 and encountering extreme cold weather.

After completing the Bathurst Inlet Patrol, Insp. French’s report to the Commissioner stated – “It is needless to say that this was a hard trip, for I must say that it has been the hardest trip I have ever made, and we suffered much from cold and exposure. These we felt all the more when our supplies ran out and when towards the end of our journey our deerskin clothing got the worse for the wear and hair started falling out and the winds pierced through the seams and holes.

Most of us were continually frozen about the face and hands, and with regard to snow blindness we were suffering from this more or less during the whole journey, the natives particularly showing a weakness in this direction even when wearing snow glasses, which I must say was due to the inferior quality of our glasses, but which were the best I could procure before we started.

Both myself and Sergeant Major Caulkin were in very poor shape as regards health; this was undoubtedly due to the straight meat diet which we had been on for the past six month or six weeks, eating only quantities of deer, seal and bear meat, to which we were unused to, and even this eaten mostly half raw ever since the time of our being out of coal oil for our lamps.” (page 12 – “Report of the Bathurst Inlet Patrol – 1917-1918”)

“Wolves seemed very numerous from time to time on the trip and several times our camp was attacked by them and a general melee would ensure among the dogs. At periods, these wolves would follow us for days, evidently being hungry and clean up anything left behind. They were our constant companion across the Barrens to Bathurst Inlet.” (page 13 – “Report of the Bathurst Inlet Patrol – 1917-1918”).

On May 17, 1917, the Expeditionary Team finally located the Inuit camp on the Coppermine River. Despite the initial reluctance of the Inuit to outlined the circumstances of the two murdered white men, Inspector French was able to interview all of the Inuit who were present at the time of the murder with the aid of the Expeditionary Team’s Inuit interpreter.

According to typed statements taken by Insp. French at the time, Harry Radford insisted that one of the Inuit men (Kan-e-ak) be a guide to take them west but the Inuit man refused because his was ill from falling through the ice. Consequently, Radford got angry and pulled out a dog whip and struck the Inuit man repeatedly in the face. The other white man (Street) tried to stop Radford. Radford then dragged the Inuit man to the open water and it appears to the other Inuit that the Inuit victim was going to be thrown into the icy water. Two Inuit (Ok-it-k and Hul-a-lark) ran over and stabbed Radford. Street ran off in the direction of his sled. Fearing that Street was going to retrieve a rifle, Ok-it-ok ran after him and caught him and Am-e-geal-nik stabbed him with a snow knife. Both dead white men were covered with snow and left on the ice.

Since all the witness statements were consistent and suggested provocation, Insp. French decided no arrests were warranted. The Expeditionary Team made their way back to Baker Lake. Then Insp. French and S/Major Caulkin made their way to Prince Prince Albert and arrived in Regina in August 1918.

In his final report to the Commissioner, Insp. French stated “I again respectfully wish to bring to your notice Reg. No. #4557, Sergeant-Major Caulkin, T.B. This non-commissioned officer has been of the greatest assistance to me and I was always found him absolutely trustworthy and reliable and he has at all times proved himself to be a man.”

Insp. French’s reports also provided an extensive survey of the Arctic which little had been known of the region and identified 30 new islands.

For their dedication and service in Bathurst Inlet Patrol, Insp. Frank French received the Imperial Service Order and Sergeant Major Thomas Caulkin received the Kings’ Police Medal for his courage and distinguished service. It was also recommended by the Force Comptroller that Thomas Caulkin be promoted to the rank of Inspector.

Thomas Caulkin’s medal was presented to him at Regina in September 1919 by the HRH Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII). Thomas was the first member of the Force to receive this medal.

The Prince of Wales also gave Thomas Caulkin a gift of a gold pocket watch.

The photograph illustrates of Insp. Caulkin and the Prince of Wales illustrates the height difference between the two men. According to his service file, Thomas Caulkin was 5’9”.

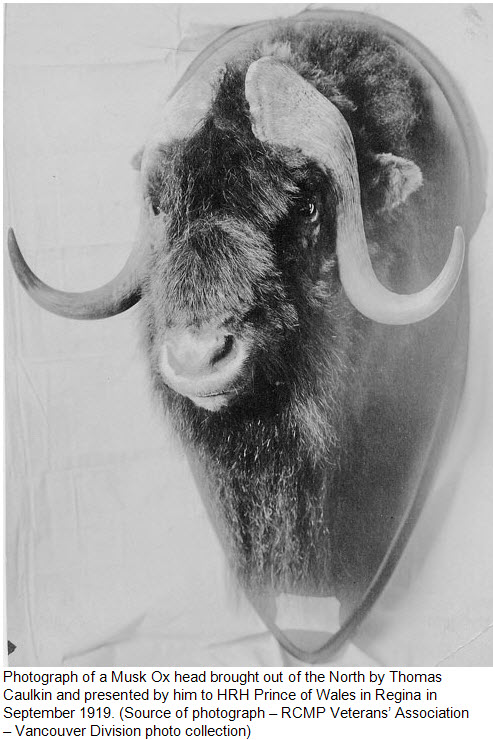

Thomas Caulkin responded by presenting to HRH Prince of Wales a mounted Musk Ox head which was brought out of the North by Thomas Caulkin.

In late August 1918, Thomas Caulkin enlisted in the newly formed “B” Squadron RNWMP which would be heading to Siberia to be a component of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force. He was pointed to the military rank Lieutenant and placed in command of Troop #3.

Ill-health in his family forced him to move to Vancouver the following May, but in September 1933 he was promoted to Superintendent and returned to the Yukon as Officer Commanding at Dawson.

Thomas Caulkin was named C.O. “N” Division at Rockcliffe in July 1937 and the next March he also was given top post of “G” Division with headquarters in Ottawa. He took over the Command of “A” Division (Ottawa) in August 1939 and was promoted to Assistant Commissioner on April 1, 1940. In November 1940, he was appointed Director of Training at Headquarters. Assistant Commissioner Caulkin retired to pension on April 19, 1942.

Assistant Commissioner George Worsley wrote a note to Thomas Caulkin’s Personnel File stating “this officer has had great norther experience and carried out one of the most hazardous patrols in the Arctic. He travelled from Chesterfield to the Arctic with Insp. French in regards to a murder. He very successfully carried out his duties for three years at Hershel Island. In Saskatchewan, he handled the Doukhobors with great tact and common sense.

In an emergency, I do not know any officer with more discretion and courage. He is most loyal to the Force and was also to me. He went with me to Siberia.”

On August 28, 1965, Thomas Caulkin passed away in Victoria and later buried at the Royal Oak Burial Park in Victoria, B.C. A photograph of his grave marker is below.

May 20, 2012

May 20, 2012