Part 6 – “B” Squadron RNWMP

The activities of “B” Squadron RNWMP and their activities are provided below and includes of members who were there. The history of the Squadron is provided in this comprehensive historical account of the Squadron’s creation, deployment, activities, challenges and return to Canada, their story is being broken down into six parts:

Part 1 – How the Force Got Involved in Going to Siberia

Part 2 – From Recruitment to Embarking on SS Monteagle

Part 3 – On Route to Vladivostok Siberia and First Impressions

Part 4 – Activities in Siberia 1918 to 1919

Part 5 – Deployment and Off-Time In Siberia

Part 6 – Demobilization and Return to Canada

Part 6 – “B” Squadron RNWMP – Demobilization in Vladivostok and Evacuation

For this article, the topics that will be outlined are as follows:

- Disease and Death

- Interaction with other Allied Troops

- YMCA Facilities & Free Time Activities

- Gymkhana

- Souvenirs

- Refugees

- Evacuation to Canada

Disease and Death

Between 1918 and 1919, Vladivostok and other Ssiberian cities possessed poor sanitation facilities and procedures. The escalating refugee population and the massive influx of Allied Intervention soldiers created a suitable environment for the spread of bacteria which resulted in cases of contagious diseases like Spanish Influenza, scarlet fever, typhus, small pox and meningitis. The lack of proper sanitation knowledge at the time left soldiers vulnerable to a variety of deadly germs.

In mid December 1918, Vladivostok was struck with a meningitis epidemic. Trooper William John Henderson (Reg. #7501) of “B” Squadron RNWMP was the first Canadian soldier to die of meningitis. He death was recorded on December 18,1919.

Trooper Henderson was buried on January 2, 1919 at the Churkin Naval Cemetery outside Vladivostok and his original grave marker is illustrated below as well as the current one which was installed in 1995 by the Commonwealth Grave Commission. As noted on both grave markers, the date of death is listed as December 29th instead of December 18.

According to Trooper John Stewart “meningitis was considered contagious and we were all quarantined for a time. To counteract the disease the doctors had the cooks the dope our food with jalopy or a similar chemical. It caused us to head to the toilet and were to report the color of our stool. Some members thought that they had contracted meningitis and many were hospitalized or placed in isolation.”

In mid January 1919, there was a typhus epidemic in Vladivostok and the surrounding area. To counter the spread of the epidemic, General George Elmsley ordered that all Canadian and British troops were to refrain from coming in close contact with local Russian citizens. Soldiers were encouraged to bathe regularly and turn-in their underwear for clean ones.

On June 1, 1919 at the Churkin Naval Cemetery, a memorial service was held for the 14 Canadian soldiers who had died while in service in Siberia. Trooper William J. Henderson was one of these 14 soldiers honoured.

The two clergymen who performed the service were Rev. (Major) Harold McCausland and Rev. (Capt.) J.M. E. Olivier. The four senior Allied Officers pictured below in the photograph were (left to right) General Chichak (Officer Commanding the Czech Legion in Vladivostok), Major General George Elmsley (Officer Commanding the Canadian Siberia Expeditionary Forces), Lt. Colonel Powell (Base Commandant) and French Officer Lt. Colonel Tassier. A photograph of these individuals are illustrated below.

“B” Squadron RNWMP members were represented at this service and were photographed. Their photograph is shown below with Major George Worsley.

The final resting spot for these 14 soldiers is illustrated in the photograph below and was taken shortly after the service.

Interaction With Other Allied Troops

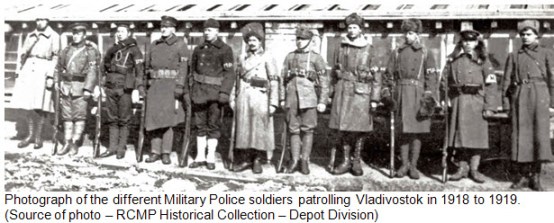

While being stationed in Siberia, members of “B” Squadron RNWMP had interaction with various soldiers from other Allied nations. This interaction ranged from performing a joint force function like Military Police Duty to socializing in and around the barrack area.In many cases, there was no common language which all soldiers communicated with. However, each soldier seemed to be able to communication their issues by a type of sign language or example.

Based on the squadron members interviewed, they provided the following comments about other Allied soldiers in Vladivostok.

British Troops

Sergeant Bob Mercer outlined that “our fellows used to help out the Hampshire Regiment. They lived in the barracks above us, you know our fellows used to do all their chores for them – chop their wood, take up their coal. Those poor devils, they didn’t have any winter clothes. These chaps came from India in tropical uniforms.”

Trooper Randolph Holding stated “for our meals, we would eat in the main mess hall with other Allied soldiers. The men of “B” Squadron met with men of the British contingent. The main topic of conversation consisted of trading stories of what each was going to do when they got back home.

The attitude of most Englishmen was that they were doing the Canadians a favour. On one occasion, I was sitting beside this Englishman who said to me ‘you know back where I come from we would never deign to speak to the likes of you.’ I replied ‘do you mean to tell me that you think yourself too good to speak to me?’ Englishman responded ‘yes’ and the fight was on. The Mess Sergeant quickly came over closely followed by General Elmsley and Major Worsley. When General George Elmsley questioned me on what started the fight – I response was ‘what would you say if I told you that he said he was too good to speak to me?’ Elmsley replied ‘I know what you mean.’ The Mess Sergeant then asked General Elmsley if he should lay a charge against me and Emsley replied no.”

French Troops

Trooper Randolph Holding outlined that “there were several fights between the Mounties and individuals of the French contingent. In all cases, the Mounties handled them easily.

Trooper Sydney Dobb (Reg. #7452) had been fooling around with a certain blonde, a French officer had done so too. They met one night at a Sporting House. The Frenchman decided that he wanted her. In the ensuing fight, Dodd administered quite a shellacking to the unhappy man much to the merriment of the on-looking Canadians.

We were delegated to setup a road block on the main road leading into Vladivostok. Our orders were to stop and check all comers. We halted a party of Frenchmen. One of them was an Air Force Officer of quite high rank. Officer uniform featured bright red britches, silver buckles and a row of bright medals. This officer objected to the questioning and tried to pass. When he was blocked in passing, the officer became mad as hell. Trooper Melvin Anthony (Reg. #7351) decided that the matter had gone far enough. Melvin was an extremely strong man. He seized the French officer and dragged him to the side fo the road, bent him over and gave him a good spanking.”

Japanese Troops

Trooper John Stewart stated that “the Japanese were very much in evidence: cavalry, artillery and infantry. None of them could speak English but we managed to converse with sign language.”

With regards to the Japanese troops, Sergeant Bob Mercer said “they were alright, we got on alright with them. They liked us, but they didn’t like the Americans.

At Second River Barracks – we used to go into Vladivostok quite regularly on the train. I can remember that Sergeant Bill Mulhall (Reg.#4748) was tight one day and he was going to throw one of the officers off the train. I don’t know if it was a Japanese officer or not. I was down at the back of the train and said –‘Bill, you better cut it out now.’ We used to go down to Vladivostok, buy a little vodka – it cost 50 cents a bottle and get the odd meal and that’s all we ever did. There was nothing else to do.”

Corporal John Stinson described the Japanese troops as “always came out on parade with full uniform and three weeks of rations in their back packs. When it came to killing Russian spies the Japanese didn’t shoot them instead they just bayoneted the spies.”

In his article entitled “Siberia 1918-1919” (RCMP Quarterly October 1941 – page 197) Assistant Commissioner Thomas Caulkin stated the “morgues were crammed with the remains of people who had been run down by speeding military vehicles operated by Japanese. The Japanese seemed to ignore completely the rights of Mongolian pedestrians. Bodies sprawled in the roadways, and prowling street-marauders invariably stripped the better-dressed corpses. Burials took place hourly.”

Czech Legion Troops

Trooper John Stewart said that “we did have some contact with some of the Czech soldiers. They were quartered in one of the large barracks that were built throughout the area. We met some of them during the time that our members were doing military police duty in and around the city area. Due to the fact that we were mounted, we policed the rougher areas of the city around the port areas.”

American Troops

Trooper Randolph Holding stated “the Americans had sustained a few casualties. Ever since the Civil War, it has been the American custom to ship the bodies of fallen soldiers home whenever possible. One day a number of sealed coffins came in and were halted for a time on the dock. After the slaying of the Czar and his family, the Russian Crown Jewels had been spirited away and hidden somewhere in Siberia. A rumor suddenly arose that the crown jewels were being smuggled out of the country inside sealed coffins. A party of Bolsheviks made a desperate rush on the dock. An emergency call when out. We Mounties on our wild western horses were the only force that could get there quickly enough. We formed up, rode through the streets and put the run on them. We never fired a shot.”

Holding further stated – “On the Manchurian border was a Japanese Bar. On one of our mounted patrols, some members of Troop 2 (“B” Squadron RNWMP) and myself had occasion to patronize this bar. Some Americans were there too. One American soldier offered money in payment for some item. He believed that he had been short changed. He pressed his claim and refused to desist. The Japanese proprietor came at him with a knife. All the Americans carried a 45 caliber Browning automatic on their hip. The American drew his Browning and shot the man. Japanese soldiers came pouring out of the rear of the place to aid their man. The Yank took his gun and calmly shot down one Japanese soldier after another. The Japanese were quite unable to down him or to take him prisoner.”

YMCA Facilities & Free Time Activities

General Elmsley was anxious to avoid problems with his Canadian troops and took steps to deploy them to military camps some distances outside Vladivostok. The intend of this isolation was to avoid the criticisms of uncivlized behaviour which the Americans has demonstrated.

The YMCA was introduced to the Western Front in World War I and was extremely popular with the Canadian troops. With the comforts and recreational activities of the YMCA, the Canadians in Europe avoided inappropriate behaviour. In preparing for the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force, the YMCA facility was a key component for this expedition.

In both Gornostai Bay Barracks and at Second River Barracks, there were YMCA facilities. For a minor fee, the YMCAs provided – sandwiches, writing stationary, local postcards, candy and tobacco. They also provided: sporting equipment (i.e. boxing gloves, hockey equipment, etc…), gramaphones, sports equipment (i.e. boxing gloves, hockey equipment, etc…) and reading rooms with an assortment of books and magazines.

Newspapers in Vladivostok were extremely limited. The Canadian Engineers did publish a newspaper called “The Siberian Sapper” and each edition sold for 1 rouble. The newspaper only contained stories of activities in and around Vladivostok. While in Siberia, Canadian troops were paid in Russian roubles.

As part of a military operation in a foreign country, the Canadian troops were subjected to censorship when it came to sending letters and parcels back to Canada. According to the Canadian Siberia Expeditionary Force General Orders No. 35 –

“All private correspondence of officers, soldiers, and attaches, which it is desired to send postage free, must be posted in the boxes or offices controlled by the Canadian Army Postal Service and clearly marked “On Active Service”

Criticism of operations, of other branches, of Allied troops or of superiors is forbidden, as are statement calculated to bring the enemy or individuals into disrepute.

It is forbidden to send home –

a) Issue tobacco and cigarettes;

b) Articles of personal clothing (whether government issue or otherwise) excep that of officers;

c) Captured trophies, except enemy helmets, caps, badges, numerals and buttons;

d) Government equipment, including that of Allied nations,

e) Anything containing cartridges, fuses and detonators, or portions of the same, or other dangerous matter.”

The following is one of the postcards which Corporal John Stinson purchased at the Second River YMCA and sent back to Canada. Note the postmark on the postcard and the censor approval.

The following is another similar postmark associated to “B” Squadron RNWMP.

Trooper John Stewart stated “often times members tempers would flare up and if it was not settled amicably, the word would go around that there was to be a fight. A ring would be squared. If possible, a doctor would be called on to attend but if none were available, the fight went on by the usual rules. The senior member present was considered to be in charge. The fight generally wound up before much blood became evident and usually ended in a draw.”

According to John Stewart, “Trumpeter Jimmy Kingston was our trumpeter and was known as ‘dirty mouth’ and had many arguments about his language.” Kingston is one of the boxes illustrated in the photographs above.

On the weekend, “B” Squadron RNWMP members would either walk to Vladivostok or take the train. Once in the city, they would walk the streets in groups and carried no firearms. However, they did carry their Lee Enfield rifle bayonet on their issued web belt.

The photograph below shows three squadron members receiving a tour of the USS Brooklyn battleship which was in the harbour during the time that the “B” Squadron members were in Vladivostok.

Trooper John Stinson recalls that his “off time on the weekends in the spring of 1919 was spent exploring the area surround the Second River barracks. On one weekend walk with other squadron members, we came across a young Russian boy fishing from a local stream.”

While fishing, the members discovered small flakes of gold. On subsequent weekends, squadron members started panning for gold using their mess tin.

Some squadron members collected enough gold to have the Austrian prisoners-of-war create a gold ring. One of the Austrian prisoners had been a jeweler in Montreal before the war and return to Austria at the outset of the war. Two such custom made rings were known to have been created and one is illustrated to the left.

On one of these walking tours of the country side, the squadron members also came across some local women washing their clothes in the same creek that the members had been fishing in. According to John Stinson, the following photograph was taken in the walnut grove near the Second River Barracks.

Corporal John Stinson further stated “we didn’t have much spare time. The constant caring for the horses and polishing our kit consumed most of our time. If you wanted to head into Vladivostok, Squadron members would have to walk there and back. In Vladivostok, food was in short supply. The only fresh meat available was wild elk.”

Trooper John Stewart outlined “I had quite a bit of contact with the Russian population and I became quite proficient with the language. I learned that they all had the same aspirations and aim in life. They were smart, keen people and very anxious to learn and were very friendly. Consorting was frowned upon by the brass. Vodka was the drink of the day. It had to be distilled and was safe to drink. The beer from the breweries was found unsafe to drink so we drank Vodka with coffee and sugar. Coffee Royals they were called. After a few one would forget that he was several thousand miles from home with the Sea of Japan frozen over and no Ice Breakers until later in the Spring.”

Trooper Randolph Rowland stated “there was a sporting house near the camp, run by a woman called ‘Lena.’ We did a lot of drinking and fighting with Russian troops here. You could get all the beer we wanted free if we called at the Russian brewery. The beer was black like stout. Vodka was 50 cents for 26 ounces.”

The nightlife in Vladivostok was a mix of seedy bars and brothels near the docks and some elegant entertainment establishments at the city’s better hotels. Sergeant Bob Mercer stated “We used to go into Vladivostok quite often. We could get passes and take the train.

Trooper Randolph Holding stated “I recall an incident in a local bar in Vladivostok. A wild and arrogant Cossack brandished a saber over the head of an American sitting at a table. The Yank pulled out a side arm and shot the Cossack full of holes.”

According to Trooper Melvine Anthony “Being the trooper receiving the princely sum of fifty cents per day paid in Russian rubles, it did not fall to our lot to attend these night clubs where females engaged in sing-songs, etc…. Neither were we able to visit the Market where choice victuals were apparently available however, cheaper places of amusement were open to the ranks until the military police placed them out of bounds.”

In Vladivostok, there was a large block in the center of town in which each apartment had a brothel. The brothels were divided racially – Chinese, Japanese, Russian, etc… A photograph of this apartment building is illustrated below.

Raymond Massey in his book entitled “When I was Young” described the Vladivostok red-district – “I visited officially with a combined patrol on several occasions, was another unforgetable horror. It was known as Kopek Hill and, of course, was out of bounds to all troops. The allied patrol was solely to apprehend violators of this quarantine. I have seen the cribs of Marseilles and some of the more repellent erotic marts of Europe and America, but there can be nothing comparable to the degradation of Vladivostok’s Kopek Hill in 1918. Every night, there was at least one murder on the Hill.”

One of the “B” Squadron members was able to get his photograph taken with the sex-trade workers of Kopek Hill.

Trooper John Stewart described the Vladivostok red-light district as “Kopek Hill was always out of bound to all troops. There armed guards posted around the Red Light district and any violator was escorted downtown to a Guardroom and escorted back to his unit by the military police.”

Stewart further stated – “it was very easy for a soldier posted away from his own locale to get into trouble. VD was very prevalent among the Russians and mixed populations where we were posted. The medical set things up that put the onus on the man if he contracted VD. You picked up a condom with your pass and had to have a preventative wash with chemicals on return if you had sex while on pass. Some men seemed to think that they had VD even if they had no physical contact with a woman. At times, I helped in Dr. Scully’s Dispensary. One man seemed to insist that he had contracted VD. Dr. Scully said to the man ‘you don’t have VD When your penis feels like barbed wire was being pulled thru it and the smoke comes out of your ears then you may have VD.’”

Gymkhana

Major George Worsley suggested to General Elmsley that a Canadian Gymkhana be performed on May 1, 1919 at the Vladivostok racetrack.

According to Trooper Randolph Holding – “Major Worsley was intensely proud of us, and he was willing to lay a bet that his Mountie boys could ride better than any others. No one could dispute him, but the two decided that the only way to prove his contention was to arrange a riding competition.” Trooper John Stewart outlined that at the time, “the Squadron were known as Worsley’s Wolves and he really took care of his men.“

The suggestion for the Gymkhana was approved and the event was advertised. The setting up and organizing of the Gymkhana was undertaken by Sergeant Margetts and other members of “B” Squadron. The schedule of events for the Gymkhana were as follows:

1) Planting the Maypole

2) Tent Pegging for NCOs & Men (10 entries per Unit) with swords;

3) Tug-of-war (open to all Allied armies and Navies);

4) Musical Chairs

5) Bucking Display by the RNWMP

6) Wrestling on Mule or Horse

7) Horse Race with 3 jumps (open to all Allied Armies)

8) Tent Pegging for Officers with swords;

9)Tug-of-war (finals)

10) Musical Ride – RNWMP

11) Roping Competition & Display by RNWMP;

12) Mounted – Picking Up The Handkerchief

13) Mule Race – Officer to ride bareback for a distance of ¼ mile;

14 Doshky Race (using a low four-wheeled open carriage pulled by two horses) – distance of open ¼ mile.

According to Trooper Randolph Holding, he won all the individual Gymkhana events and was given the Russian nickname of “Durak Katysky” – crazy devil.

In his report to the Commission, Major George Worsley wrote – “On the first of May, we organized a Gymkhana and gave a musical ride and other sports. This created great interest among the Russians, who numbered quite 10,000. It was held on the Race Course and was attended by all the notable people of Vladivostok, General Otani took the salute and General Horvath, the Russian Commander-in-Chief was also present.

The RNWMP carried off all the prizes except the tug-of-war and General Elmsley sent for me and gave great praise to the Squadron for its work in connection with the affair. Sergeant Margetts, the Farrier Sergeant, was of great assistance and showed great energy, as did the other officers, NCOs and men.

On the day of the Gymkhana, when General Horvath was returning, a bomb was thrown at his carriage, wounding several. The Bolsheviks who did this were captured by Canadians and I was about 100 yards off when it occurred. “

According to the “B” Squadron RNWMP General Order’s, two officers, 60 men and 65 horses participated in the Gymkhana. Photographs taken of the “B” Squadron RNWMP members at the Gymkhana are shown below.

The ‘tug-a-war’ event was won by members of the 260th Battalion of the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force.

The following is a photograph of the Vladivostok crowd shortly after the Gymkhana was over.

Souvenirs

While in Vladivostok, Corporal John Stinson was active in seeking out souvenirs to take home. According to John “we barter for various items. The most valuable item which the Russians would trade us for were our underwear and related wash-up items. In exchange for our stuff we would receive Russian diamonds, semi-precious gems and other interesting items.”

Most of the items that he acquired were from the Chinese market in Vladivostok and was similar to our modern day flea market. The following is a photograph of this market with two Squadron members.

The illustrated to the left are items that Corporal John Stinson was able to trade for while being stationed in Vladivostok.

In addition, he traded for two short Russian Cossack swords. Just prior to his death, he sold these swords and was surprised at the amount of money he received for them.

John Stinson’s trading was not limited to the Chinese market. He also traded with the German and Austrian prisoners-of-war who were assigned to do labour work at both Gornostai Bay Barracks and Second Rivers Barracks. One notable item he acquired from a German prisoner-of-war was the following oil painting of Vladivostok. Apparently, the German only a single hair to create the painting.

The label on the reverse of the oil painting states “Vlaidovstok Siberia. Scene from the Eastern edge of the Vladivostok harbour, painted by German prisoner of war, and as seen from the prison quarters. City is to the left and below. Races were held on track in Spring of 1919. Stables to left and right centre where RNWMP Squadron were quartered on arrival and also quartered before departure.

Roadway and Valley swing to the left as shown in scene, continue on to Gornostai Bay on Sea Coast about 8 miles, where there was a large Military Camp with Barracks complete, underground fortifications installed but not armed. Here most of the Canadian Forces spent the winter. RNWMP Squaqdron moved to Triratcha (Two Rivers) in early spring. The hills shown in painting have underground fortifications to protect the harbour. – J.V. Stinson Reg. No. 6256.”

Refugees

Between 1918 and 1919, the Trans-Siberian Railway was one of the primary exit methods of escaping from the Bolshevik’s ‘reign-of-terror.’ From Omsk to Vladivostok, refugees lived in empty boxcars which were stationary on side tracks. When there was a military need for boxcars, the refugees were evicted and forced to find shelter elsewhere.

On the Trans-Baikal line, there were 10,000 American build boxcars sitting idle on a sidetrack. At the time, 80% of the locomotives were sitting idle because of the lack of coal. West bound trains were carrying equipment for the New Russian Army and the coal had been provided by the Americans who reactivated a coal mine at Suschan which was just outside Vladivostok. On the return trip, the boxcars were usually filled with refugees. Most of the refugees were children with a few adults – women and the elderly. Men had been conscripted into either the Bolshevik or New White Russian army. The following is a photograph of one of those refugee trains which pulled into Vladivostok at the time.

The following is another photograph of a passenger train which arrived in Vladivostok during the time that “B” Squadron RNWMP members were there.

Trooper John Stewart recalls being delegated to work with the International Red Cross workers and dealt with the arriving refugees. First they were “checked them for disease. The next move was into a delouser and their clothing were taken away and they were provided with new clothes which had been sent out by aid societies. When we had a large enough group together we marched them out along the roads to barracks that had been cleaned up by refugees that had arrived earlier. They were provided with cooking tools and bedding.” Food kitchens were setup by the International Red Cross and aid agencies to feed the refugees.

Stewart also stated “I visited some of the refugee barracks and they all seemed to be very pleased to be away from fear of the advancing Red Army. What happened to them when the protection of the Allied troops was withdrawn would be another story.” Many of these refugees tried to stowaway on one of the many departing Allied ships.

According to John Stinson, “the Russian refugee kids were everywhere begging for food.” The following photograph is that of some squadron members with some of the refugee children who were hanging around the Second River Barracks.”

One young Russian boy was adopted by Trooper Walter Charleson (Reg. #6471). His name was Nicky. The following photograph is a members of Troop #4 with Nicky.

With regards to Nicky, Trooper John Stewart stated “he had the run of the camp but stayed close to Troop 4. Troop 4 members had a tailor cut down a uniform (suspected that the uniform cut down was that of Trooper Henderson) for him and he was always well behaved but he was always kept hidden when any office or senior NCO was present. After leaving Siberia on the boat, Nicky showed up one day in the mess but again he was kept out of sight. Before arriving in Canada, several other stowaways showed up as they had been hiding most of the trip and were given food to eat.”

According to Corporal John Stinson “Nicky came to Canada with the returning “B” Squadron members and originally settled in Brandon Manitoba. He adopted the surname of Samson and eventually drifted to the United States and settled in Hollywood California.”

Many Allied troops sought permission to marry attractive Russian women. However, the Canadian government declined these requests. According to Trooper John Stewart – “there was one man named Kelf (Trooper William H. Kelf – Reg. #7356) who we considered slightly retarded. He married a Russian girl and too his discharge in Siberia. He was on the dock when we sailed still in his Canadian uniform and did not seem happy to see us leave. When Sergeant Margetts detial returned to Canada, I heard that Kelf had stowed away on a boat and returned to Canada but did not bring his wife along.”

Research revealed that Kelf was discharged on May 19, 1919 at Vladivostok with Trooper Sterling L. Squires (Reg. # 7528).

Evacuation to Canada

Major George Worsley in his report to the Commissioner stated “about the middle of April, we received information that we would be returned to Canada in the course of a few months, and commenced returning stores to Ordnance early in May. We marched to East Barracks on the 21st of May 1919.”

On the 5th of June, the Squadron embarked in the S.S. “Monteagle” five officers and 139 other ranks and after an unevenful voyage of seventeen days landed at Vancouver. They were notified that we would be required for strike duty in Vancouver.

Trooper John Stewart stated – “on arrival in Vancouver, we expected to be demobilized from the army but there was a general strike across Canada, so we were re-armed and billeted in what was known as the Beatty Street Armouries. We did troop patrols etc… around Vancouver for a month and the group was gradually dispersed.

I arrived back in Regina and reported to the military headquarters and received discharge from the Army. Next step was to report to Depot. Having engaged for 3 years in 1918, I was told to go to the tailor shop and get fitted with a new uniform.

For the balance of the summer at Depot I did mounted drill, instructing recruits on prairie west of the CPR.

In the fall of 1919, the remaining members of the squadron were in Depot and we were formed into two groups. One troop went to Fort McLeod under command of Supt. R. Douglas and my group went to Brandon Manitoba where we were billeted in the local armoury and stabled in the winter fair barns.

Life became very dull. Daily routine consisted of doing foot and mounted drill. For lack of action, quite a few constables went over the hill come payday. The Quartermaster posted a sign outside the door asking all deserters to leave their kit in the canvas sheet outside the door with their name on the sheet. No check up was ever made to trace the deserters. In September 1920, I bought my discharge for $50 and got a job in civilian life.

All members of “B” Squadron RNWMP were qualified to receive the British War Medal 1914-1920 and the Victory medal.

Although “B” Squadron members did not participate in any military battles in Russia, members of the squadron distinguished themselves and displayed a high standard which contributed the reputation of the Force.

In of view of their contributions to the Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force, the battle honour of Siberia 1918-1919 was added to the Force’s Guidon as illustrated below.

April 8, 2012

April 8, 2012