RNWMP: Volunteerism & Patriotism In World War I

For this November 11 Remembrance Day, we are highlighting the contributions and sacrifices made by past members of the Force.

Volunteerism and patriotism have been hallmarks of the Force since its creation in 1873. At no time in the history of the Force has volunteerism and patriotism been as high as it was during World War I.

IMPACT ON MEMBERS VOLUNTEERING

With the outbreak of the war on July 28, 1914, the Royal Northwest Mounted Police (RNWMP) establishment stood at 1,268 members. These members were distributed throughout western Canada and in the north: Alberta – 304; Saskatchewan – 870; Northwest Territories – 53; Yukon – 53; Manitoba – 26.

With 173,568 German and Austrian aliens living in Western Canada in 1914, the Canadian government decided to increase the Force establishment by 434 members for one year. These members would be designated as the Reserve Division and would be based in Regina. In September 1914, they commenced their training at the old Indian School about a mile and half from “Depot” barracks in Regina. The intent of this Division was to deploy members to combat issues or concerns relating to the enemy aliens.

At the time, the government “felt that an increase of the force was necessary to impress upon all races that good order would be preserved, and that our alien enemies who quietly pursued their ordinary vocations and observed strictly their obligations as residents of this country, would receive adequate protection.”[1]

By September 1915, Commissioner Bowen Perry reported to the Canadian government that the enemy aliens gave no cause for anxiety and a comparatively small number were interned. Therefore, the Reserve Division members were discharged from the Force. The majority of these release members joined various battalions and regiments in the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

As with many patriotic Canadians, members of the Force were also anxious to volunteer for World War I. In 1914 and 1915, Commissioner Bowen Perry permitted many members to leave the Force with a ‘free discharge’ to rejoin their British regiment. These regiments included:

-

- Coldstream Guards,

-

- King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry regiment,

-

- Irish Guards,

-

- Leinster Regiment,

-

- Oxford & Bucks Light Infantry,

-

- 18th (Queen Mary’s Own) Hussars,

-

- Royal Artillery,

-

- Royal Berkshire Regiment,

-

- Royal Sussex Regiment,

-

- Scots Guards,

-

- Welsh Guards, and

-

- York & Lancaster Regiment

One such member was Constable Michael O’Leary (Reg. # 5685) who received a free discharge from the Force on September 22, 1914 when he was recalled to Cork Ireland for the mobilization of his Irish Guards Regiment. O’Leary would on January 1, 1915 distinguish himself by crossing ‘no-man’s land’ in Flanders to knock out two German machine gun positions. For this act of bravery, he was awarded the Victoria Cross which was presented to him by His Majesty King George V at Buckingham Palace.

Other Force members sought a similar ‘free discharge’ to join the Canadian Expeditionary Force while others failed to renew their three term in the Force or purchased their own discharge.

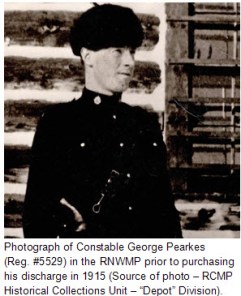

One of these members was George Randolph Pearkes (Reg. #5529) who paid $50.00 to purchase his discharge from the Force. Upon leaving, he joined the Canadian Mounted Rifle Battalion in 1915. On the western front, he was wounded five times. His actions on October 30/31, 1917, during the Battle of Passchendalele Belgium, won him the Victoria Cross. He would also receive the Military Cross for his bravery.

In 1915, the Commissioner reported to the Canadian government that the Force strength had dropped to 987 (Alberta 406, Saskatchewan 559; Northwest Territories – 2; Yukon – 20 & Manitoba 0). This decrease and the inability to recruit suitable recruits was attributed to aggressive recruiting by the Canadian Expeditionary Forces. For 1915, 305 failed to renew their 3 year term in the Force; 27 purchased their discharge and 34 deserted.

In an effort to stem the tide of Force members not re-engaging in the Force and volunteering to serve overseas in World War I, Commissioner Perry included comment in his Report of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police of 1916 which was also distributed to all RNWMP Posts:

”…all members of the force must remember that the service which they are now rendering to the Dominion and to the Empire is not less important than that which they would perform if actually serving at the front. Further, it is a service which can only be efficiently performed by a force which has been trained in the discharge of the duties which it is called upon to undertake. For these reasons the Prime Minister has found himself unable to consent to the retirement from the force of many officers and men who have asked that permission for the purpose of enlistment.”[2]

In 1916, Superintendent Walton Routledge, Officer Commanding “F” Division, outlined “war-time enlistments by men of the Force had so depleted the ranks that many outlying detachments were closed and even divisional quarters were understaffed.”[3]

In July 1916, Commissioner Bowen Perry met with Prime Minister Robert Borden and outlined the crisis facing the Force:

-

- increased security expectation for the Force to patrol the Canadian-US border because the United States (U.S.) was a neutral country and contained many German sympathizers;

-

- increased demands from the provincial governments of Saskatchewan and Alberta to aggressively enforce liquor prohibition and other provincial statutes; and

-

- decreasing number of suitable individuals to replace members who volunteered for service with the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

In view of this crisis, the Prime Minister sought the consent from Premiers of Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan to an early termination of the RNWMP provincial policing agreement on November 10, 1916. All provincial Premiers agreed to the early termination. As such, each province was obligated to create their own provincial police force. All RNWMP members were withdrawn from provincial police duties on between January 1 and April 1, 1917.

On April 17, 1917, the U.S. entered World War I on the side of the Allies. As such, there was no longer a requirement to continue with patrols of the Canada-U.S. Border. As such, the work of Force members was significantly reduced.

In 1917 Commissioner’s report to government, Commissioner Perry outlined “the Force consisted of 42 officers, 603 non-commissioned officers and constables and 675 horses: as compared with the same with the same date a year earlier this represents a decrease of four officers, 137 non-commissioned officers and constable and 129 horses. The decrease in the force, Commissioner Perry stated, is due to the war conditions. No less than 234 members of the force took their discharge on the expiration of their term of service or by purchase, and the majority of these enlisted for overseas service. His observes that owing to the shortage of labor and the high wages paid, it will be difficult to replace these men.[4]

GOVERNMENT APPROVES FORCE TO SEND UNITS TO WAR

Commissioner Bowen Perry continued to promote the suggestion that the members of the Force should be permitted to form and send a cavalry regiment to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. For many months, Commissioner Perry had “been agitating for an opportunity to show their mettle in actual warfare” and “made all sorts of proposals to the government, from the joining as mounted rifle or cavalry regiments for work in France, to the raising of squadrons of horse for work in Mesopotamia or Palestine.”[5]

On April 6th, 1918, the Canadian government finally approved the creation of a Cavalry Draft – RNWMP for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It consisted of: 12 RNWMP officers and 726 NCOs and constables. On these NCOs and constables, 81 NCOs and 150 men were Force members and 495 were new recruits. On May 15, 1918, all Cavalry Draft members were sworn in to the Canadian Expeditionary Force. By the end of May, the draft left Regina in two separate trains heading to Montreal to board a ship taking them to Europe.

With this transfer, the Force was left with 483 members (Alberta -109 members; Saskatchewan – 315 members; Northwest Territories – 17 members; Yukon – 41 members and Manitoba – 1 members).

Then on August 12, 1918, the Canadian government authorized the establishment of “B” Squadron RNWMP which would be transferred to the Canadian Expeditionary Force for deployment to Canadian Siberian Expeditionary Force. This Squadron consisted of: 5 officers and 175 members (62 Regular Members & 113 recruits especially engaged for the squadron). Check here for the six part article on “B” Squadron RNWMP.

With the departure of “B” Squadron members, the total establishment of the Force was reduced to: 303 members (35 officers and 268 members) who were distributed to: Alberta – 128; Saskatchewan – 8; Yukon – 7 and Manitoba – 5). With this reduced strength, 87 of 113 Detachments were closed.

MEMBERS IN THE CANADIAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCE

From September 1914 to November 11, 1918, members left the Force and joined various Canadian Expeditionary Force battalions, regiments and other units such as:

1st Battalion, 3rd Battalion, 4th Battalion, 5th Battalion, 6th Battalion, 7th Battalion, 8th Battalion, 10th Battalion, 12th Battalion, 15th Battalion, 16th Battalion, 20th Battalion, 21st Battalion, 23rd Battalion, 24th Battalion, 26th Battalion, 27th Battalion, 28th Battalion, 29th Battalion, 31st Battalion, 43rd Battalion, 44th Battalion, 46th Battalion, 47th Battalion, 49th Battalion, 50th Battalion, 51st Battalion, 52nd Battalion, 54th Battalion, 56th Battalion, 60th Battalion, 63rd Battalion, 66th Battalion, 68th Battalion, 72nd Battalion, 79th Battalion, 82nd Battalion, 85th Battalion, 94th Battalion,

100th Battalion, 102nd Battalion, 138th Battalion, 144th Battalion, 151st Battalion, 172nd Battalion, 176th Battalion, 179th Battalion, 180th Battalion, 184th Battalion, 187th Battalion, 188th Battalion,191st Battalion, 194th Battalion, 195th Battalion, 196th Battalion,

202nd Battalion, 210th Battalion, 217th Battalion, 218th Battalion, 231st Battalion, 238th Battalion, 243rd Battalion, 244th Battalion and 249th Battalion.

19th Alberta Dragoons,

Ammunition Column,

Brigade Field Ambulance,

“B” Squadron RNWMP (Siberian Expeditionary Force),

1st Canadian Divisional HQ,

Canadian Engineers,

Canadian Field Artillery,

Canadian Garrison Regiment,

Canadian Light Horse,

Canadian Machine Gun Corps,

Canadian Motor Machine Gun,

Canadian Mounted Rifles,

#50 Cavalry Draft (RNWMP),

Fort Gary Horse,

Lord Strathcona Horse Regiment,

Princess Patricia’s Light Infantry Regiment,

Royal Flying Corps,

Royal Canadian Dragoons,

Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, and

Seaforth Highlanders Regiment.

PREPARING FOR WAR

Many of the Western Canadian Battalions were sent to Camp Hughes for their initial military training. This camp was located in southern Manitoba. After departing Canada, they were shipped to the Canadian military base at Shorncliffe England. Shorncliffe was a training base and staging point for Canadian troops heading to the western front.

WESTERN FRONT

The battlefield conditions were well beyond the expectation of all Canadians. On the western front, it was a stalemate between the Allies and the German-Austrian armies. Each side had established a network of trenches and the distance between the trenches was known as ‘no-man’s-land.’ Passage through ‘no-man’s-land’ was impeded by water filled bomb craters, mines and fields of barbed wire.

From 1915 to 1918, each side would pepper their enemy with poison gas and artillery shells. Positions were defended by integrated and cross-fire machine gun positions. Advances made resulted in thousands of casualties on each side.

Each month, hundreds of soldiers were killed by enemy snipers. It was not uncommon to have 300+ soldiers killed a month from snipers.

Night raids across no-man’s-land would result in hand-to-hand combat with their enemy to: gain intelligence, capture prisoners, and check on the enemy’s position.

The British steel helmet was only introduced in October 1915 and would be worn for the rest of the war. Prior to October 1915, British and Canadian soldiers had only worn their regimental hat as protection against the rain.

While maintaining their position in trenches, Canadian troops would frequently stand in water for days. This prolonged standing resulted in ‘trench foot’ which caused their feet to turn numb and turn either red or blue in colour. At the time, the best defense was to change their wool socks frequently.

When it came to daylight advances across ‘no-man’s land’ – the artillery first would pound the enemy positions with thousands of shells hoping to knockout: enemy concrete bunkers, barbed wire, artillery batteries and machine gun positions. Once the artillery barrage ceased, it was time for the Canadians troops to climb out of their trenches and commence walking across ‘no-man’s land’ hoping that the barbed wire had been cut and the enemy’s machine positions had been knocked out.

CASAULTIES

With little or no protection for the soldiers against enemy artillery and machine guns, the casualties were very high.

Upon receiving notice that soldiers were wounded, the battalion stretcher bearers would endeavour safely find and retrieve all wounded soldiers. The wounded would be brought to the Advanced Dressing Station which was situated near the front lines.

If wounded soldiers could not be retrieved safely or located, they were left in ‘no-man’s- land.’ Wounded men left in ‘no-man’s-land‘ would sometimes cry out to their comrades to come and retrieve them. However with the threat of daylight enemy snipers, the wounded would be left to die or to be retrieved the following night.

When soldiers were able to walk – they made their way to the Advanced Dressing Station for preliminary treatment and possibly to a Casualty Clearing Station.

Depending on the number and seriousness of the wounded soldiers, the Medical Officer would have the injured evacuated by horse ambulance to hospital facilities farther beyond the lines.

All Advanced Dressing Stations or Casualty Clearing Stations buried the soldiers who died of their wounds in a nearby cemetery. In and around Ypres Belgium, there are over 180 such World War I cemeteries.

The Canadian casualties and death toll on the western front was staggering:

-

- April 1915 – 2nd Battle of Ypres – 6,000 casualties with 2,000 killed;

-

- July to November 1916 – Battle of the Somme – 24,029 Canadian casualties;

-

- April 1917 – Battle of Vimy Ridge – 10,602 casualties; 3,598 killed and 7,004 wounded;

-

- October 1917 – Battle of Passchendaele – 15,654 casualties with over 4,000 dead, in 16 days of fighting; and

-

- August to November 1918 (last Hundred Day Battle) – 46,000 casualties.

WAR BURIALS

For World War I, there had been 418,052[6] Canadian troops sent overseas. Of this total, the consequences of this war were as follows:

-

- Killed in Action – 34,496;

-

- Died of Wounds – 17,182;

-

- Presumed dead from enemy action – 4,960;

-

- Missing – 4,368;

-

- Repatriated (prisoners of war) – 4,500; and

-

- Wounded – 132,550.

In 1915, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission was established to record and register the burial locations of British and Commonwealth soldiers killed in World War I. Soldiers were initially buried close to the location that they died. Later, many remains were exhumed and moved to larger cemeteries.

After World War I, the Canadian government decided that all their soldiers who died in Europe would remain in Europe.

For soldiers whose identity and burial location was known, they received the following Commonwealth War Grave grave marker:

If the human remains of a Canadian soldier could not be identified, the following grave marker was provided:

In cases where no human remains were found or the Canadian soldier’s remains were not identified, their name would appear on either the Menin Memorial Gate at Ypres Belgium or on the Vimy Memorial.

The total number of Force members who volunteered for service in WWI exceeded 2,500 of whom at least 146 were killed or died of their wounds:

-

- 136 died in France and Belgium;

- 8 died in England;

- 1 died in Egypt (Lt. Col. Cecil Longueville Snow with the British Intelligence Corps – Reg. #1359);

- 1 died at Vladivostok Siberia (William Henderson – Reg. #7501)

This total does not include the wounded ex-members who returned to Canada and who would died of their wounds.

Of the 136 ex-members, the human remains of 44 ex-members could not be located. As such, their names are noted on the Menin Memorial Gate (22) in Ypres Belgium and on the Vimy Memorial (21) in France. Their names are listed below:

MENIN GATE MEMORIAL

Force Reg.# Name

4826 Alexander BAILEY

5612 Victor BROWN

2036 Herbert William DONALDSON

5549 Ludovic DUHAMEL

5375 Barry Pevensey DUKE (British Lieut. with Royal Sussex Regiment)

5818 James EDGE

4782 William John ELTON

5240 Harry FORMAN

2957 Herbert Philip HILTON (British Captain with Middlesex Regiment)

4811 Edward Harold KEMP

4139 John Wentworth KERSLEY

4401 Arthur Edwin LAWRENCE

2861 Frank LEWIS

4912 Francis Oswald LLOYD

4666 Robert Henry MAGEE

5257 George Leigh McALLUM

6140 James MOWBRAY

3367 John ROWLEY

O.14 Alfred Ernest SHAW

5307 George William TALLENTS

2897 Paul George TOFFT

5237 James Guy WHEATLEY

VIMY RIDGE

Force Reg.# Name

5926 Edward BARNETT

5945 Thomas George BAVIN

5392 Lawrence Stanley CARRICK

5932 Oscar Stanley BLAKSTAD

5444 Harry James COOK

6302 Stephen BOOTH

5089 George Edward DUNKLEY

5791 Antoine deRoussy DeSALES

5501 Reginald George ELAND

5389 Frederick William HAWKES

5015 Gerald Howard HOLBROOKE

5189 Leonard Elridge JERROM

4375 Harold Robertson KISSACK

3986 Robert Graham MacDONALD

6147 Cecil Oliver PRICE

3708 James Allan PROFIT

3321 Harry SERGEANT

4031 George VICKERY

5238 George Douglas WAITE

6035 James Robert WALLACE

5735 Stanley Edward WILLIAMS

The following is an example why some of these bodies were not located:

The death of Lt. Colonel Alfred Ernest Shaw (RNWMP Reg. O.14) outlines the horrible battle conditions the Canadian Force Expeditionary forces were experiencing in the Ypres Salient. He commanded the 1st Canadian Mounted Rifle Battalion “until he was killed in action at Maple Copse in the Ypres Salient on June 2nd, 1916. At the time of his death, he was gallantly rallying his men to make a final stand. On that terrible day only one officer and 60 men of his unit came out of that disastrous engagement. The enemy had concentrated 1,000 guns on that particular mile and a half of trench and simply blew the battalion off the face of the earth.”[7]

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Today, many Canadians don’t know much about our country’s involvement in World War I. However in Europe, the people of France and Belgium still hold memorials to pay tribute to the soldiers who came in World War I when their countries were being invaded by Germany and Austria.

For example at the Menin Memorial Gate, there is a nightly memorial service with the Ypres Fire Department trumpeters playing last post. Each night, there are hundreds of locals and tourists in attendance. This service has been ongoing since 1927.

The memory of World War I and the soldiers who gave their lives to defend Belgium and France is not forgotten. It is important for all Canadians to pause for two minutes during this year’s Remembrance Day to remember our past ex-RNWMP comrades who stepped forward to volunteer and serve their country.

[1] Perry, Bowen – “Report of the Royal North West Mounted Police 1915” (page 8)

[2] Canada, Sessional Papers, n. 28, The Report Of the Royal Northwest Mounted Police – 1916 (page 8)

[3] Anderson, Frank – “Saskatchewan Provincial Police” Frontier Book No. 26 (6)

[4] Winnipeg Free Press article September 1917 – “DECREASE IN FORCE OF MOUNTED POLICE: Annual Report Tabled By Hon. N.W. Rowell.”

[5] Winnipeg Free Press article dated April 29, 1918 entitled “Mounted Police For Battlefront: Three Squadrons TO Be Recruited From Famous Riders Of Western Plains.”

[6] Statistics Canada website – http://www65.statcan.gc.ca/acyb02/1947/acyb02_19471126002-eng.htm

[7] Scout, “Veterans Of The R.N.W.M.P. Won Added Fame Overseas” – Scarlet & Gold Magazine – 8th edition (1926) – page 31.

November 5, 2017

November 5, 2017