The Most Northerly Route – Looking Back 70 Years

This article was provided to us by Doreen Larsen Riedel (daughter of the late Supt. Henry Larsen). Her article provides details of the RCMP Vessel St. Roch’s journey through the Arctic and the challenges faced by the original crew members. This article originally appeared in the Argonauta (Volume XXXI Number 4 Autumn 2014).

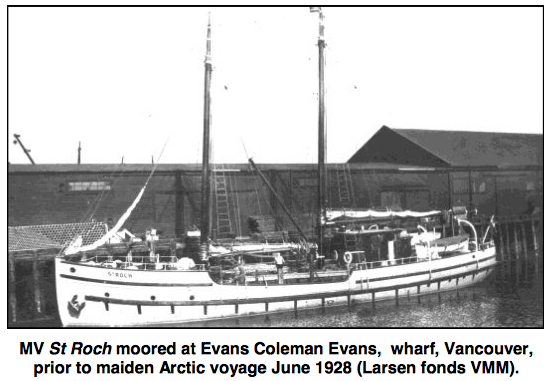

For over 400 years, economic factors drove the British and European search for the Northwest Passage. By the time of the Victorian age at the end of the Napoleonic wars, many British naval officers and men had become unemployed, creating pressure for northern expeditions to provide employment for them. Yet it took many more decades before the Norwegian polar explorer, Roald Amundsen, made the first documented, successful transit of the sea route above the North American continent in 1905-06. This transit was not in a big warship or trading vessel with hundreds of men, but in a small Norwegian fishing vessel with a crew of 8. Nearly forty more years passed before the next two transits. These were made by Henry Larsen, a Norwegian Canadian, in a small wooden Royal Canadian Mounted Police schooner, St Roch, especially built as a floating police detachment, and with a crew of 7 and 10.

Ten years later, when the Northwest Passage became important for defence rea- sons, the Canadian icebreaker HMCS Labrador, the American icebreakers USCGS Storis, Bramble, Spar and American submarines USS Nautilus and Seadragon, took up the icy challenge. By the end of 2012, 135 vessels (excluding submarines) had crossed the Arctic Circle on each side of the North American continent, the points that officially mark the limits of the Northwest Passage.(1) Today we hear about so many cruise ships, research vessels, military vessels and commercial ships passing through these waters, as well as open rowboats, canoes, kayaks and small yachts, that we almost dismiss the difficulties of the earlier voyages.

The historic west to east voyage of the St Roch in 1940-42 is reasonably well known, although the breadth and difficulties of jobs carried out by the crews of that ship over its whole career, from 1928-1948, are not. The 1944 voyage is usually dismissed as taking only 86 days, leaving the impression that it was an easy passage. However on this 70th anniversary year of that voyage it is my intention to dispel this notion.

Up until the mid-1950s, members of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police assigned to Arctic service, including those on the St Roch, carried out activities outside the normal range of police work. They conducted regular patrols by dog team to conduct census, monitor game, issue licences and permits, distribute family allowances, carry mail, and check living conditions in Inuit communities. They administered federal regulations, enforced territorial ordinances, acted as notaries public, commissioners of oaths and inspectors of weights and measures.

They wrote extensive reports, monitored weather, transmitted messages by radio, recorded flow in rivers, collected biological specimens, determined suitability of sites for posts and harbours, built new posts and relocated others. They transported children to school and cared for the sick, transporting the very ill to hospitals at Aklavik. They also moved trappers, ministers, priests and other Royal Canadian Mounted Police members from one post to another. They acted as coroners, justices of the peace and occasionally investigated murders or transported prisoners. They explored and mapped large and remote Arctic areas, raised and trained dogs for their patrol use, hunted walrus, bear, seals and fished for themselves and their sled dogs. During the long winters they dressed and travelled in native fashion, usually hiring a local man to go along to help. Their objective was the maintenance of Canada’s sovereignty over the Canadian Arctic.

The crew of the St Roch was appointed in the same manner as any other Royal Canadian Mounted Police detachment, usually for a year or two, and without prior maritime training. In addition to the myriad of responsibilities previously outlined, the crew loaded supplies in Vancouver or at the mouth of the McKenzie River and carried them to land detachments along Coronation Gulf. By 1948, St. Roch had over wintered 11 years. At the beginning of each of these winters, the crew selected a harbour and built a protective cover over the ship. They collected water for winter from freshwater pools on the sea ice or cut blocks of ice from nearby lakes. When spring approached, they used a pick and shovel to remove ice from around the hull and particularly from around the propeller, then scraped and repainted the entire ship.

On seeing the St Roch as she is today, preserved in the Vancouver Maritime Museum safe on dry land, one can hardly imagine the experience of the crew aboard the ship when they voyaged in ice-ridden, dangerous northern waters years ago. The interior space was small and cramped; most of the crew were berthed below deck. It was impossible to see over the bow from the wheelhouse, a serious defect when navigating in ice. There was no satellite system, radar, weather report, ice reconnaissance, coast guard patrol or search and rescue. They carried all food and fuel supplies north with them. Radio contact extended about 200 miles, so messages were relayed between various posts. When the main engine was not running, kerosene or gasoline lamps were used until batteries were installed for electric light in 1940. The waters they passed through were largely uncharted, there was no depth sounder. The single magnetic compass in the tiny wheelhouse was impossible to use for taking bearings. Larsen was the only navigator until 1940. When the weather was good, he took his sightings using a sextant and a pocket stop watch because the chronometer in the wheel- house was inaccessible. He spent many hours observing from the crow’s nest, signalling directions by hand to a man on the deck who then passed the information to the man at the wheel, who in turn relayed orders to the engine room. Larsen, aware of the deficiencies of the ship wrote this after its historic 1940-42 voyage through the Northwest Passage: “In Halifax, the St Roch, being ugly, slow and uncomfortable to live on, was now like an unwanted stepchild, and looked upon with a criticising eye by people who did not know her many good qualities in a tight spot and especially in the waters she was built for.”

By summer of 1943, the eastern Arctic had become important for defence purposes; airstrips and weather stations were being built. But many Royal Canadian Mounted Police and Hudson Bay Company posts had already closed and there was a shortage of ships to carry in supplies. So the St Roch was assigned to carry all she could handle. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police had no men to spare for crew. Larsen was authorized to pick up whatever men he could.

The following year (1944), after discussions in Ottawa with the army, navy and air force, Department of Transport and various government officials dealing with Arctic defence, Larsen received orders to take the St Roch westward to Vancouver through the more northerly Northwest Passage route. This voyage was not intended to be a feat of navigation, but rather to maintain Canadian sovereignty over her Arctic Islands. Over 35 years had passed since Captain JE Bernier, officially patrolling the Arctic on behalf of Canada, had claimed the territory between its east and west mainland borders as well as the entire Arctic Archipelago.(2) Now increasing numbers of Americans were in the Canadian Arctic without Canadian oversight. Could the Royal Canadian Mounted Police posts at Craig and Dundas Harbours be reopened; and in light of increased German U-boat threat, could the posts be supplied from the west? Might new detachments be established on islands along the more northern route, possibly at Winter Harbour on Melville Island? Larsen was directed to determine the topographical description of the land, and information about tidal ranges, water depth, direction of ice movement and currents, and the possibility of fog along the route. Just as in 1940, the 7,295 mile mission was secret except to a few government and military officials. The route he was to use was into Melville Sound then south through Prince of Wales Strait. The stretch through Melville Sound and McClure Strait had never before been navigated by any ship.

During the winter of 1943-44, the St Roch underwent refit at Dartmouth. During the war years, the shipyard was fully committed to work on navy and transport ships and it was a constant struggle to get supplies and equipment for St. Roch. The American government gave permission for Union Diesel to provide a 300 HP engine to replace the underpowered 150 HP engine. To carry out this work, the small deck house and part of the afterdeck were removed which provided an opportunity for Larsen’s other requested alterations to be made. While frozen in at Pasley Bay in 1941-42, Larsen had measured up the ship and made plans for a larger deck house providing space for several cabins, a wireless room, mess room and galley above deck, and allowing for more space below for fuel and provisions. He wanted to replace the original main mast and dangerous sail with a shorter mast near the stern on which to carry a small riding or storm sail.

Larsen faced a shortage of suitable men as crew. Corporal Bill Peters and Pat Hunt, from the1940-42 voyage, volunteered as engineer and clerk. Seventy year old Rudolph Johnson, a Dane who had traded for years in the Arctic on several Hudson’s Bay Company vessels, signed up as second engineer, and 65 year old arctic trader, Ole Andreassen, who had travelled with Stefansson, joined as mate. The others had never seen the Arctic, but at least two, Frank Matthews and Stan McKenzie, young fishermen from Port Aux Basque, Newfoundland, had been to sea. James Diplock was the only constable the Royal Canadian Mounted Police could spare. Two young fellows recently released from the air force joined them, L.G Russill as wireless operator and G.B. Dickens as cook. Russill had just finished radio school, but had never sent a ship to shore message. Bill Cashin, barely 17, an assistant to machinist on ships and who had to get his mother’s consent to go, made up the complement.

But recruiting crew was the least of the problems. Their canned food which bore the proud legend, “Prepared Especially for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police” proved so salty that even the dogs wouldn’t eat it. All the cases were the same. Too late to replace it, and here they were, ready to leave for the Arctic on a voyage that might take a year or two, with their canned meat supply unfit to eat.

On July 19th 1944 Roch departed from Dartmouth shipyard. Larsen wrote: “I would venture to say, that never had anyone prepared to leave for an Arctic voyage which included the instruction to navigate the Northwest Passage under a more trying condition of unreadiness.” They were already late heading out into the Arctic. Sea trials were few and short, with not time enough for defects to show up. Rather, the defects developed a few hours later. The engine didn’t run well; the engine cooling system pipes leaked, the joints squirted water, and rubber connections pulsated like bellows. The engine room became flooded. They returned to Dartmouth. Two days later they set off again. The funnel and exhaust silencer extending through the deck became hot and the iron plate they sat on scorched the deck; the pitch in the deck seams around the plate was running. The water hose had to be kept running around it so the deck wouldn’t catch fire. Water leaked into the engine room. This time they headed for the naval base at Sydney NS. By the time they reached Curling Cove, Newfoundland for a final refuelling, they were over a week behind schedule. After more repairs, they headed north again. A few days later their eggs were found to be going bad; they had not been processed in water glass. The sailors checked the “fresh” vegetables. Potatoes, cabbages, turnips and onions – all rotten!

The usual heavy ice drift hampered them along the Labrador coast while the egg shaped ship rolled considerably. The more powerful engine improved speed, but they shipped more water. Determining their position was “by guess and by God” because it was too foggy to shoot the sun, the magnetic compass wandered all over, usually pointing towards the bow of the ship, and the newly installed gyro fluctuated with changing errors. Fourteen days after first leaving Dartmouth they were only at the south end of Baffin Island in tightly packed ice and burning up precious fuel. Knowing from sealers and whalers that the Greenland coast was usually clear at that time of year, Larsen headed there. It was clear and sunny with open waters except for a few giant icebergs. A bit north of Disco Island conditions looked improved westward. Then, scheduled to call at Pond Inlet, they cut across towards Baffin Island, but heavy ice forced them to shut down and drift with the pack. Thick freezing fog covered the ship and clung to the rigging.

Suddenly a huge polar bear, well over a thousand pounds, loomed out of a fog on an ice flow. Larsen shot the bear; now they had meat. But they were again stopped for 3 days by a huge field of ice, unbroken to the shore.

By August 12, they anchored at Pond Inlet and unloaded supplies for the police detachment. In case they had to overwinter, they took an Inuit family on board, Joe Panipakoocho, who had worked for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police at Pond Inlet, his wife Leitia, his mother Paninikpa, three little girls (aged nine, eight and four) and 15 year old step son, Arreak, their belongings and 17 dogs.

The family set up a tent over the hatch. Joe had no knowledge of a ship the size of St Roch, but Larsen described Joe and Arreak as natural born seamen. Leaving Pond Inlet in heavy fog, they headed for Dundas Harbour on Devon Island, running into a southeast gale with snow and sleet as they crossed the strong current of Navy Board Inlet and Lancaster Sound. Ice encased the ship; the dogs, gathered into a little cargo scow and covered with a tarpaulin, were so miserable that they didn’t even fight. For hours they cruised back and forth under the lea of a mile long, flat iceberg for shelter until the gale subsided. Late afternoon of August 18 they anchored in front of the deserted, very exposed police detachment, located at a small, ice free bight to the east of Dundas Harbour. Here they posted the first cylinder; prior to the journey, preparations were made for Larsen and his crew to build a series of cairns and to deposit brass cylinders containing a record of their visit, along with various papers and ordinances dealing with Canadian administration of Arctic islands into the cairns.

Leaving Dundas Harbour, they followed the straight cliffs of the Devon Island coast westward in a hard blowing wind and poor visibility to an opening that led to a long inlet ending in a deep, calm and protected cove. Here were three ancient stone and bone dwellings and grassy mounds, remains of people the Inuit call Tunit. It was impossible to determine their location from their old British Admiralty chart, but when cylinder #2 was located by crew of CGS Labrador (3) in 1968, it was determined to be Stratton Inlet.

After they left the sheltered inlet at 4 am, they again met heavy snowfalls, sometimes obscuring the land. The weather cleared while crossing Maxwell Bay from where Prince Regent Inlet appeared to be ice free. Late that afternoon they anchored in Erebus Bay of Beechey Island. Here in 1855 a cenotaph had been erected by Belcher and in 1857, a memorial to Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames and their crew had been installed by M’Clintock on behalf of Lady Franklin.(4)(5) Here were the remains of Northumberland House cache, established in 1854 by Commander W.S. Pullen of HMS North Star and of the small yacht Mary, originally left on Devon Island by Sir John Ross, for the use of chance survivors of the Franklin expedition. Captain Bernier had visited the place in 1906 and left his record in a cairn on an elevated plateau referred to as “Franklin’s cairn”. Cylinder # 3, deposited by the flagpole, was found in 1957 by Capt T.C. Pullen and Lt J.A. MacNeil of HMCS Labrador.(6)

Leaving Beechey Island, they crossed Wellington Channel. Thick snow prevented them from landing at Resolute Bay on Corn- wallis Island and heavy ice swept towards them. Proceeding westward, they spotted numerous walrus on the ice between Griffith Island and Resolute Bay and four of them provided a welcome change in diet for men and dogs.

Thirty-eight days after first leaving Dartmouth, they had passed Somerville and Brown Islands and were about 8 miles east of Cape Cockburn on Bathurst island and became trapped in the thickly packed ice moving eastward with great speed. It carried them backwards about twenty miles before they managed to get loose. Working their way inshore they anchored behind some shoals on which heavy ice had grounded, but which broke the flow of drift ice. Finally the wind changed, clearing the ice from the shore, enabling them to follow a lead up to Cape Cockburn. Here they built a cairn and deposited Cylinder #4 (which was collected by the Labrador during a geological survey in 1968). Their position was recorded as approximate. Navigation had been very difficult for several days; constant snow fall and fog obscured the sun and land most of the time. Their magnetic compass was unresponsive with its North point fixed on the ship’s bow regardless of direction so they were navigating by dead reckoning. The ice in Melville Sound was tightly packed to the west and south. Working northward in Austin Channel, alternately steaming and drifting, they reached Schomberg Point. In my father’s personal diary, he recorded that he was dead tired from lack of sleep.

When good lead appeared to the north end of Bryam Martin Island they were able to land and build Cairn #5. Constantly sounding by hand lead, they followed the island’s northern point then crossed to Melville Island. Now there was little ice and they enjoyed the first clear weather in days. Griffith Point on Melville was a long sand spit without rocks; Cylinder #6 was placed on a large, solitary boulder 2-3 miles from the spit and heaped up with sod. During the night and next forenoon they again worked through heavy snow with little visibility, and at midnight reached Palmer Point of Skene Bay. The place was a mass of boulders. Cylinder #7 was deposited in a pyramid of rocks looking much like a cairn. The weather cleared briefly the following day allowing them to proceed to Dealey Island where Captain Henry Kellet had wintered in HMS Resolute in 1853. On the top of the island, Kellet had left a cairn consisting of a huge pile of rocks on which is raised a spar surmounted by three barrels. The stone walls of the massive cache he also built still stood, but the roof had long since fallen in. At one end were iron tanks of hard, square ships biscuits (some wet and soggy), bearing a broad arrow stamp denoting them as property of the British Navy. Canned meat and vegetables stacked up and covered with sod, formed part of one wall. In the middle was a conglomeration of broken barrels of flour, clothing, coal, salt beef, broken hardwood pulleys for ships blocks, and sea boots. Outside were scattered leather sea boots, soggy navy clothing, and broken barrels of chocolate, peas and beans. Two Ross Army rifles and ammunition were found on the beach, the latter left by Bernier in 1909.

They found wooden headstones of three men who had died during Kellet’s stay and took samples of the cache for analysis, collecting Bernier’s record, and depositing their own (cylinder #8) by the flag pole and barrel. On the beach they found an 18 foot oak, light Pram left by Bernier. It was sheathed in unrusted metal and shod with two steel runners. Because it was superior to the St Roch’s own, clumsy, heavy and leaky skiff, they exchanged them. Winter Harbour, their next destination, lay west of Dealey Island. A wide expanse along the shore was ice free, but to the south, tightly packed ice could be seen in Melville Sound

In a few hours they passed the small headland named Cape Bounty by Lt William Parry, who passed there in 1819 with his ships Hecla and Gripper. Parry had been awarded the 5000 pounds the British Admiralty had offered to the first man who in the quest for the Northwest Passage passed the 110th meridian west of Greenwich, England. When Larsen and his crew reached Winter Harbour, they identified Parry Rock by the names of several seamen and HM Hecla and Gripper carved into it. The Northwest Passage had been within Parry’s grasp in 1819, but on reaching Cape Providence, his group met impenetrable ice and wintered at Winter Harbour. Parry Rock bears a large copper plate inscribed with the Union Jack and the Canadian Coat of Arms which Bernier erected in 1909 when he took possession of the Arctic Archipelago lying north of the continent and between 60°W to 141°W and up to Lat 90°N. St Roch was the first ship to visit since 1910 when Bernier had endeavoured to negotiate the Northwest Passage, but had been forced back by impenetrable floes in M’Clure Strait. St Roch’s Cylinder #9 was found on Parry Rock by the Franklin Probe Society in July 1962.

St. Roch left Winter Harbour on August 30, enjoying a clear day and a clear run for 30 miles, but they struck gigantic floes of old ice from the Polar Sea itself just as Parry and Bernier had in past voyages.There was no turning back. Fog, mist and heavy rain descended upon them. They moored to a large flow and waited. Now they were in waters never before traversed by any vessel, the eastern entrance of M’Clure Strait. Alternately tying up to the ice and drifting, hampered by thick fog and sleet, they gradually worked southward. The weather became almost dead calm. The ice flow they were moored to revolved slowly in an anticlockwise direction, repeatedly bringing them to the north side of the flow. When the fog lifted briefly they glimpsed the entrance to Prince of Wales Strait, but solid ice lay ahead of them. They alternately steamed and drifted, moored and waited in the heavy fog and ice. Two days later, they spied land ahead through the fog. They moored to a grounded ice flow close to shore to await better weather. The merry-go-round drift they had been through made it impossible to determine which side of Prince of Wales Strait they were on. By Septem- ber 3 they determined they were in Richard Collinson Inlet of Victoria Island and followed the coast westward to the strait. Now the weather was wonderfully clear with sunshine, the only fine day during the entire passage. By night fall on September 4 they were in familiar territory off the southern end of the Strait. Leaving Holman Island before midnight on September 5, they were now in a field of tightly packed ice along the mainland shore. Their “home waters” didn’t welcome them. Buffeted by strong winds, they crawled westward through heavy ice in a blinding snow storm, driven close to shore.

Two days later they tied up to grounded ice at Toker Point. The following day, fog impeded them, lifting briefly at noon to reveal that their way west was completely closed. Worse, fresh north winds were driving more ice upon them. Larsen decided to head for Tuktoyakuk. The shallow waters and strong current of the McKenzie River kept a large stretch of water open there.

The channel into the “Tuk” harbour is narrow, crooked and risky even with shore markers, but in the darkness the markers could not be seen and they grounded on the mud flats. They managed to back off and anchored in 3 fathoms to await daylight. Larsen hated to do this because he knew a gale was on its way. It arrived swiftly with pouring rain. By morning to seaward was nothing but ice with a shallow stretch of water inside. The mud quickly became churned up and the ship rolled violently. They needed deeper water, but could easily have been washed up onto the mud if they got too far leeward. With the swell and good luck they were fortunately lifted over the shallows.

Once in the harbour they dropped anchor and let out all their cable. The gale reached hurricane proportions in a matter of minutes. The water rose 10 feet, flooding the Hudson Bay Company buildings, washing away goods, equipment, and buildings and drowning 17 Inuit dogs staked on a nearby island. A small island of peat and willow drifted by them. They had entered the harbour just in time to save themselves from certain destruction. The following day revealed that the sand spit was completely changed. Blue permafrost was seen where land had been torn away.

Mackenzie Bay was a solid mass ice. A passing aircraft reported unbroken ice to Herschel Island. Seemingly fated to spend the winter in Tuk, they set out nets for to trap winter food for the dogs.

A week later a fresh wind blew up from the east and northeast and Larsen decided to try to cross to Herschel Island. They barely floated out of the now shallower harbour and then steamed all night through leads in the ice. Some flows were 10 miles long and one carried 7 polar bears. Near the abandoned settlement of Herschel Island, fog returned again. The land was snowed under and the harbour choked with ice. That night a severe blow came up, but great slabs of grounded ice served as a breakwater. They installed the Inuit family in one of the empty houses and unloaded fuel and excess supplies. News from Point Barrow was that the ice was packed solid and no ships could get out. The season was the worst in years. Then a slight easterly wind came up. Larsen wrote, “That was just what I needed and after all these years I knew exactly what it would do in the way of loosening the ice pack, and leaving a narrow lead along the shore”. They immediately ceased unloading and prepared to depart.

September 21, 1230 they were underway. Larsen prayed the breeze would hold until they got around Point Barrow. Fog again descended. They couldn’t see the sun. Depending on the lead line, they groped their way along the north coast. Larsen knew the coast well, having sounded almost every inch of it over the years and he knew that if they could keep to 7 fathoms of water it would take them right to Point Barrow. The evening of September 23, news came from Barrow that with the now changing winds, the little lead that had opened was rapidly closing. It was too late to turn back now. Taking chances greater than he ordinarily would have, Larsen “ordered the engineer to give her all he had.” Accurate soundings were most important and the lead line soon became covered with ice. On the 15 foot mark Larsen tied a piece of bunting that would be visible in the light they hung over the side, close to the water’s edge. Nearing Point Barrow, the ice was closer and closer to the beach and the water shoaled alarmingly. Suddenly at 0145h the lead-man shouted, “We’ve lost bottom”. That was the call Larsen had been waiting for. Soon they saw the welcoming lights of the Cape Smyth settlement. The ice was pressing in close to the shore; they were in less than 15 feet of water with no room to turn around. They were now in touch by radio. People had turned on the lights along the shore to assist the crew in finding their way along the shoreline.

They continued straight on until 27 September when they finally reached King Is- land, Alaska where an Eskimo village perched like a bird’s nest on its rocky shore, they hoped to get a bit of rest, but saw no signs of life. No one responded to their signals. Larsen ordered, “Hoist the Stars and Stripes!” The village suddenly came to life. Kayaks were put out to greet them. By-passing Dutch Harbour they instead docked at Akutan; from then on it was mostly plain sailing. It was at Akutan where Larsen was able to be out of his clothes to sleep for the first time since leaving Nova Scotia.

At 1900h on October 16, [1944] her hull pitted, scarred and dirty, St Roch crept into her home port.

Stretched across the bridge was a large white pennant the youngest crew member, Billy Cashin, had made from a Royal Canadian Mounted Police bed sheet and green ship’s paint, proudly announcing their achievement. So ended the long treacherous journey – one which most Canadians know very little about, but that helped to establish sovereignty in Canada’s north.

Footnotes

- R. K. Headland, Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2012 Navigation Season, Re- vised 3 March 2013, Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER

- Alan MacEachern, “J.E. Bernier’s Claims to Fame”, Canadian Journal of the History of Science, Technology and Medicine,, 2010, (Vol. 33, No. 2) p. 43‐73.

- Formerly Wind-class icebreaker HMCS Labrador, Canada’s first modern and powerful icebreaker: commissioned in 1954.

- David Murphy, The Arctic Fox: Francis Leopold‐McClintock, Discoverer of the Fate of Franklin, 2004, p. 119.

- Beechey Island is one of the most important heritage locations in Canada and in the history of arctic exploration by the Royal Navy in the nineteenth century according to Brian D. Powell, The memorials on Beechey Island, Nunavut, Canada: an historical and pictorial survey Polar Record, 2006 (Vol. 42, No. 04) p. 325‐333.

- Graham Rowley, “Captain TC. Pullen, RCN: Polar Navigator,” The Northern Mariner/Le Marin du nord, April 1992, (Vol. 2, No. 2), p. 29‐49

January 27, 2015

January 27, 2015